Our Alumni

At Tilting Futures, the immersion program is just the beginning. You’ll graduate into a lifelong community of inspiring alumni who are at colleges and companies across the globe.

Prince Bashangezi

Democratic Republic of the Congo | Academy ‘21

“I learned how to develop a project, drive it forward, measure its success, and effectively connect others to the cause.”

Prince brought internet access to the refugee camp where he grew up by winning a grant through a Tilting Futures partner.

Talia Katz

United States | Senegal ‘13

“This program helped me demonstrate to funding agencies that I was prepared to take on a research project in another country at such a young age.”

Talia Katz is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at John Hopkins University. Her work explores the role of art under the pressures of violence, war, and displacement.

WHERE OUR ALUMNI WORK

A powerful global community

CONNECT

Connect with a global community of changemakers through our events, monthly digest, community hub, and alumni gatherings.

INSPIRE

Join expert-led workshops, career conversations, and more. Get access to programs like Boulevard, Readocracy, and the Institute for Economics & Peace.

AMPLIFY

Bring attention to your projects. Leverage Tilting Futures’ platform to amplify your voice and impact.

ENGAGE

Join us in building a movement! Get involved as an Alumni Ambassador, moderate an event, join the conversation on social media, or make a donation.

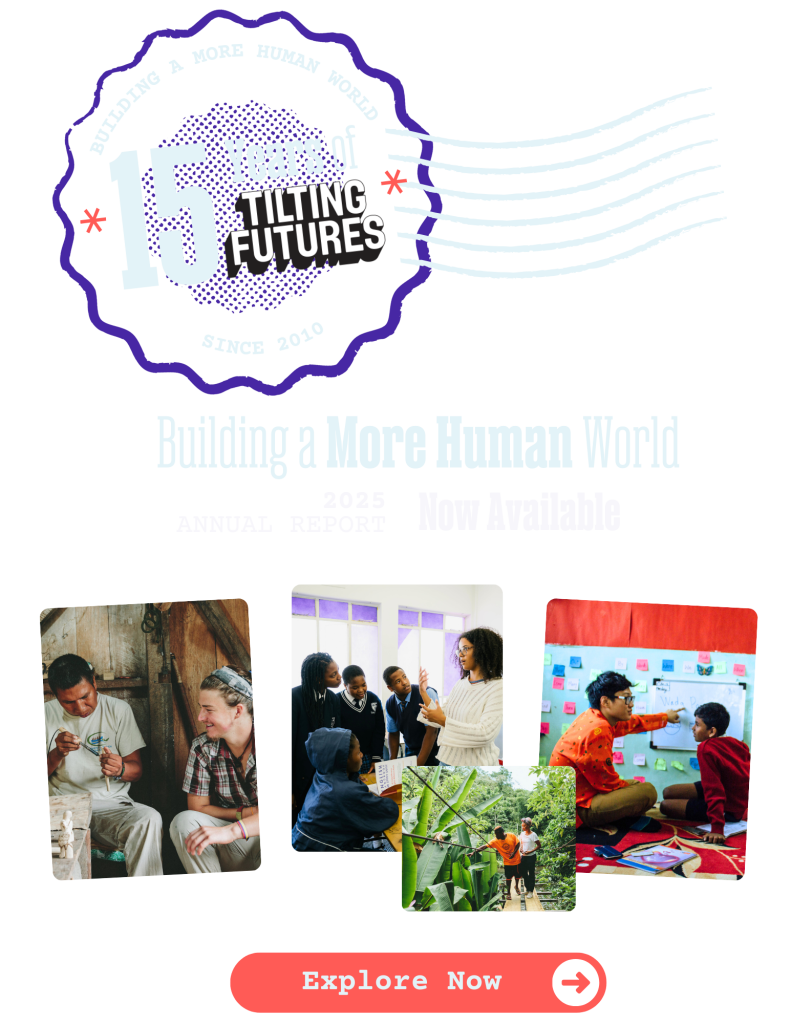

Since 2010, we’ve run three innovative programs and operated in six different countries. Across years and programs, our alumni are united by a hopeful determination that together we can build a better future.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the virtual Academy brought together students worldwide around our signature curriculum

(2020-2022)

from Take Action Lab

Our current program, Take Action Lab focuses on human rights in South Africa

(2022-Present)

In our first decade, Fellows immersed in communities across Brazil, Ecuador, Guatemala, India, and Senegal

(2010-2020)

GLOBAL OPPORTUNITIES

Circle of Service in Partnership with the Peace Corps

Are you a Tilting Futures alum with U.S. citizenship eager to continue creating global impact? Our new Circle of Service partnership means you’re eligible for an expedited application process with the Peace Corps. Learn more about this program and apply today!